- Home

- Laia Jufresa

Umami Page 3

Umami Read online

Page 3

‘One day I just said enough is enough to the product mentality, you know? It’s not that I’m giving up playing, I just don’t need to package it. I devote myself to the music now, not the orchestra. I’m all about the process now.’

‘And the orchestra lets you?’ Marina had asked, for the sake of saying something.

‘They gave me unpaid leave,’ Linda said. ‘And you know what? For not one of my pregnancies did I get that. Musicians don’t believe in babies, but in mourning, sure. I blame Wagner.’

2002

Amaranth, the plant to which I’ve dedicated the best part of my forty years as a researcher, has a ludicrous name. One that, now I’m a widower, makes me seethe.

Amaranthus, the generic name, comes from the Greek amaranthos, which means ‘flower that never fades’.

*

I’ve been a widower since last Mexican Day of the Dead: November 2 2001. That morning my wife lay admiring the customary altar I’d set up in the room. It was a bit makeshift: three vases of dandelions and Mexican marigolds, and not much else, because neither of us was in the mood for the traditional sugar skulls. Noelia adjusted her turban (she hated me seeing her bald) and pointed to the altar.

‘Nah, nah, nah-nah-nah,’ she sang.

‘Nah, nah, nah-nah-nah, what?’ I asked.

‘I beat them.’

‘Beat who?’

‘The dead,’ she said. ‘They came and they went, and they didn’t take me.’

But that afternoon, when I took her up her Nescafé with milk, Noelia had gone with them. Sometimes I think that what hurts most is that she went without me there. With me downstairs, standing like a muppet by the stove, waiting for the water to boil. The damn, chalky, chlorinated Mexico City water, at its damn 2,260 meters above sea level, taking its own sweet time to make the kettle whistle.

*

Noelia’s surname was Vargas Vargas. Her parents were both from Michoacán, but one was from the city of Morelia and the other Uruapan, and at any given opportunity they’d publicly avow that they were not cousins. They had five children, and ate lunch together every day. He was a cardiologist and had a clinic just around the corner. She was a homemaker and her sole peccadillo was playing bridge three times a week, where she’d fritter away a healthy slice of the grocery budget. But they never wanted for anything. Apart from grandchildren. On our part at least, we left them wanting.

By way of explanation, or consolation perhaps, my mother-in-law used to remind me in apologetic tones that, ‘Ever since she was a little girl, Noelia wanted to be a daughter and nothing else.’ According to her version of events, while Noelia’s little friends played at being Mommy with their dolls, she preferred to be her friends’ daughter, or the doll’s friend, or even the doll’s daughter; a move that was generally deemed unacceptable by her playmates, who would ask, with that particular harsh cruelty of little girls, ‘When have you ever seen a Mommy that pretty?’

Bizarrely, my wife, who blamed so many of her issues on being a childless child, would never get into this topic with me. She refused to discuss the fact that it was her mother who first used the term ‘only a daughter’ in reference to her. And it occurs to me now, darling Noelia, that your obsession may well spring from there; that it wasn’t something you chose exactly, but rather that your own mother drummed into you.

‘Don’t be an Inuit, Alfonso,’ says my wife, who, every time she feels the need to say ‘idiot’, substitutes the word with another random noun beginning with i.

Substituted it, she substituted it. I have to relearn how to conjugate now that she’s not around. But the thing is, when I wrote it down just now, ‘Don’t be an Inuit, Alfonso’, it was as if it wasn’t me who’d written it. It was as if she were saying it herself.

Perhaps that’s what the new black machine is for. Yes, that’s why they brought it to me: so Noelia will talk to me again.

*

I have a colleague at the institute who, aged fifty-two, married a woman of twenty-seven. But any sense of shame only hit them when she turned thirty and he fifty-five, because all of a sudden it no longer required any mathematical effort to work out the age gap: the quarter of a century between them was laid bare for all to see. Something more or less like this happened to us in the mews. Numbers confounded us when, in the same year my wife died, aged fifty-five, so did the five-year-old daughter of my tenants. Noelia’s death seemed almost reasonable compared to Luz’s, which was so incomprehensible, so unfair. But death is never fair, nor is fifty-five old.

I’ll also make use of my new machine to moan, if I so choose, about having been left a widower before my time, and about the fact that nobody paid me the slightest attention. The person who showed the most concern was our friend Páez. But Páez was more caught up in his own sorrow than mine. He would call me up late at night, drunk, consumed by the discovery that not even his generation was immortal.

‘I can’t sleep thinking about you alone in that house, my friend. Promise me you won’t stop showering,’ he would say.

And then the inconsiderate ass went and died too. Noelia always used to say that bad things happen in threes.

They couldn’t have cared less at work, either.

‘Take a year’s sabbatical,’ they told me. ‘Languish in life. Rot away in your damned urban milpa, which we never had any faith in anyway. Go and wilt among your amaranths.’

And I, ever compliant, said, ‘Where do I sign?’

A first-class howler, because now I’m losing my mind all day in the house. I don’t even have Internet. I’m sure the black machine should hook up to Wi-Fi but so far I haven’t made any attempt to understand how that works. I prefer the television. At least I know how to turn it on. These last weeks I’ve got into the mid-morning programming. It is tremendous.

I hadn’t heard anything from the institute since the start of my year’s sabbatical. Then, two weeks ago, they came and left a machine. I’m told it’s my 2001 research bonus, even though that god-awful year finished six months ago and was the least productive of my academic life. Unless ‘Living With Your Wife’s Pancreatic Cancer’ and then ‘First Baby-Steps as a Widower’ can be considered research topics. I imagine they were sent an extra machine by mistake and that they can’t send it back because then, of course, they would be charged. All the bureaucratic details of the institute are counterintuitive, but the people who run it act as if it were perfectly coherent. For example, they tell me that I have to use the machine for my research, presumably to get to grips with online resources and move into the twenty-first century, but then they send a delivery boy to pass on the message. That’s right, along with the laptop, the delivery boy brought a hard-copy agreement. Because nothing can happen in the institute unless it’s written in an agreement and printed on an official letterhead with the Director’s signature at the bottom.

The kid pulled out a cardboard box from his Tsuru, not so different from a pizza box, and handed it to me.

‘It’s a laptop, sir. In the office they told me to say you gotta use it for your research.’

‘And my sabbatical?’ I said.

‘Hey, listen, man, they ain’t told me nothing more than to make the drop and go.’

‘So “make the drop” and go,’ I told him.

He put it down and I left it in there on the doorstep in its box. That was two weeks ago.

Then finally today I rented out Bitter House. It’s gone to a skinny young thing who says she’s a painter. She brought me my check and, by way of guarantee, the deed to an Italian restaurant in Xalapa. I know it’s Italian because it’s called Pisa. And this is a play on words, according to the girl, who told me that beyond referring to the famous tower, it’s also how Xalapans pronounce the word pizza.

‘Although, strictly speaking they say pitsa,’ she explained, ‘but if my parents had called it that, it would have been too obvious we were jerking around.’

‘Ah,’ I replied.

I only hope she

doesn’t take drugs. Or that she takes them quietly and pays me on time. It’s not much to ask, considering the price I gave her. She was happy with everything save the color of the fronts of the houses.

‘I’m thinking of painting them,’ I lied.

The funny thing is that after signing – which we did in the Mustard Mug, because it’s next door to the stationary shop and we had to photocopy her documents – I left feeling good. Productive, let’s say. Or nearly. On my way back I bought a six-pack and some chips, and took The Girls out onto the backyard’s terrace. Having positioned them so they could preside over the ceremony, I opened the box – the one now propping up my feet, and a very comfy innovation, I might add – and went about setting up the machine. I have to say I felt a bit excited as I opened it. Only a little bit, but even so, the most excited I’ve been so far in 2002.

The machine is black and lighter than any of my computers to date. I’m writing on it now. I was particularly proud of how swiftly I set it up. Set it up is a manner of speaking. The truth is I plugged it in and that was that. The only work involved was removing the plastic and polystyrene. For a name, I chose Nina Simone. My other computer, the old elephant in my office where I wrote every one of my articles from the last decade, was called Dumbo. In Dumbo’s Windows my user icon was a photo of me, but someone from tech support at the institute uploaded it for me. My expertise doesn’t stretch that far. In Nina Simone’s Windows my user icon is the factory setting: an inflatable duck. Microsoft Word just tried to change inflatable to infallible. Word’s an Inuit.

Dammit! Noelia used to come up with a different word beginning with i every time. I’m just not made of the same stuff.

I’m an invalid, an invader, an island.

*

When she was little, Noelia didn’t want to be a doctor like her dad, but rather an actress like a great aunt of hers who had made her name in silent movies. After high school Noelia signed up to an intensive theater course, but on the second week, when the time came for her to improvise in front of the group, she turned bright red, couldn’t utter a word and suffered a paroxysmal tachycardia. A bloody awful thing: it’s when your heart beats more than 160 times a minute. It’s certainly happened to me, but never, in fact, to Noe. Noe was just self-diagnosing: she had a flair for it even then.

After her disastrous course she enrolled at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where, after a number of grueling years – even today, having spent my whole life around doctors, I still don’t know how they do it – she qualified as a cardiologist. Noelia would say, ‘That’s consultant cardiac electrophysiologist to you.’

Noelia told me all this the first time we had dinner together. It seemed strange to me that public speaking could be more frightening to her than being confronted with someone’s insides.

‘Why medicine?’ I asked. ‘Why not something easier?’

It was 1972 and we were in a restaurant in the Zona Rosa, when the Zona Rosa was still a decent sort of neighborhood, not like now. Even though, truth be told, I don’t know what it’s like now because it’s been years since I ventured out there.

‘I had this absurd idea that in medicine you get to really know people, on a one-to-one level,’ said my wife, who that night was no more than a girl I’d just met.

She downed her tequila.

‘I suppose I’ve always been a bit naive.’

And that was when the penny dropped that she was a flirt, something you wouldn’t have guessed at first. And naive? You bet. But only about certain things, and with the kind of ingenuousness which didn’t remotely diminish her razor-sharp mind. She was naive when it suited her. Noelia was very practical but a little scatterbrained. She was openhearted, cunning and gorgeous-looking. She was also, on that first night and for the following three weeks, a vegetarian.

She liked one-to-ones. She liked going out for coffee with people. She liked to sneak out for a cigarette with the nurses and get the latest gossip on, as she put it, ‘everyone and their mother’. She stopped being vegetarian because she adored meat. Even raw meat. Steak tartare. She always ordered Kibbeh on her birthday. I haven’t gone back to the city center because it stirs up too many memories of our birthday trips to El Edén. Nobody warns you about this, but the dead, or at least some of them, take customs, decades, whole neighborhoods with them. Things you thought you shared but which turned out to be theirs. When death does you part, it’s also the end of what’s mine is yours.

Noelia didn’t mention on that first evening that her father had been the top dog at the Heart and Vascular Hospital in Mexico City before opening his own clinic in Michoacán. Nor that it was there, at the tender age of twelve, that she learned to read holters, which means detect arrhythmias. Nor did she mention over dinner that she was one of just five (five!) specialists in her area in the entire country. She told me the following morning. We were naked on the sofa in her living room, and before I even knew it I’d knocked back my coffee, scrambled into my clothes and hotfooted it out of her apartment. I didn’t even ask for her number. In other words, as she accurately diagnosed it the next time we saw each other almost a year later, I ‘chickened out, like a chicken’.

To say I chickened out is an understatement, of course. In reality, and using another of Noelia’s expressions, I shit my pants. I was petrified, and only came to understand the root of my panic later, when I began to analyze who I’d spent the subsequent twelve months bedding: all of them well-read, highly educated young women. Basically, my students. I was even going to marry one of them: Memphis, as Noelia nicknamed her years later when they finally met (I think because of the boots she was wearing, or maybe it was the haircut, what do I know?). Mercifully, just before the wedding I had a dream. I was a bit macho, yes, a chicken, certainly, but before either of those things I was superstitious as hell: having received the message, I knew I had to heed my subconscious, so I turned up unannounced at Noelia’s apartment. For a minute she didn’t recognize me. Then she played hard-to-get for a while, like two weeks. But as time went on we became so inseparable, so glued at the hip, that now I can’t understand. On my job at the National Institute for History and Anthropology, on my grant from the National Organization of Researchers, on all those qualifications which supposedly mean that I know how to deal with complex questions, I swear I don’t get it. I don’t understand how I’m still breathing if one of my lungs has been ripped out.

The dream I had. Noelia was standing in a doorway with lots of light behind her. That was it. It was a still dream, but crystal frickin’ clear in its message. Threatening even. When I woke up, still next to Memphis, I knew I had two options: I could take the easy route, or the happy one. An epiphany, you might call it. Incidentally, the only one I ever had in my life.

*

Noelia had a soft spot for sayings and idioms. If ever there was something I didn’t get – which was often – she would sigh and say, ‘Shall I spell it out for you?’ I remember one time Noe sent me flowers to the institute for a prize I’d won, and on the little card she’d written, ‘You’re the bee’s knees’.

But sometimes the sayings and idioms were home-grown, without her having consulted anyone. For example, she tended to come out with, ‘A scalpel in hand is worth two in the belly.’ And I always thought this was a medical saying, but Páez assured me that he’d only ever heard it come from Noe’s mouth and that no one in the hospital really knew what it meant; some thought it was something like ‘better to be the doctor than the patient’, while others understood it as ‘better to take your time while operating than to botch it in a hurry’, et cetera, et cetera.

On the other hand, Noelia couldn’t abide riddles. Or board games. And general-knowledge quizzes were her absolute bugbear. They put her in a flap and she’d forget the answers then get all pissy. We once lost Trivial Pursuit because she couldn’t name the capital of Canada. She also loathed sports and any form of exercise. She had a fervent dislike of dust. And insects. For her, the very definition of e

vil was a cockroach. And she didn’t clean, but rather paid someone to clean for her. Doña Sara stopped working for me a few months ago with the excuse that she’d always planned to move back to her home village, but really I think seeing me in such a state depressed her. I paid her her severance check; she set up a taco stand. She did the right thing. Hers really were the best tacos in the world. And it’s a good thing too, I think, for me to deal with my own waste.

For much of my life I really did believe I was the bee’s knees, because unlike my colleagues I liked to get my hands dirty actually planting the species we lectured on. I always kept a milpa in the backyard because, in my opinion, if you’re going to say that an entire civilization ate such-and-such thing then you have to know what that thing tastes like, how it grows, how much water it needs. If you’re going to go around proclaiming the symbiosis of the three sisters, you have to grab a hold of your shovel and take each one in turn: first the corn, then the beans, and after that the squash. But now I see my whole agricultural phase differently: I had time on my hands. Time not taken up by youngsters. Time not taken up folding clothes. It’s so obvious but only now do I fully understand that it’s easier to get your hands dirty when you’ve got someone to clean everything else for you. But there you go, I was always the most bourgeois of anthropologists.

These days, when I hit the hay, quite often the only productive thing I’ve done all day is wash the dishes I used, or clean up the studio, or take out the trash. I suck at it, but I give it my all. Once The Girls are in the stroller, I push them to whichever part of the house is messiest. I like to have witnesses.

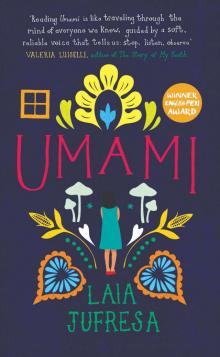

Umami

Umami